Everyone Thinks They're Doing Good

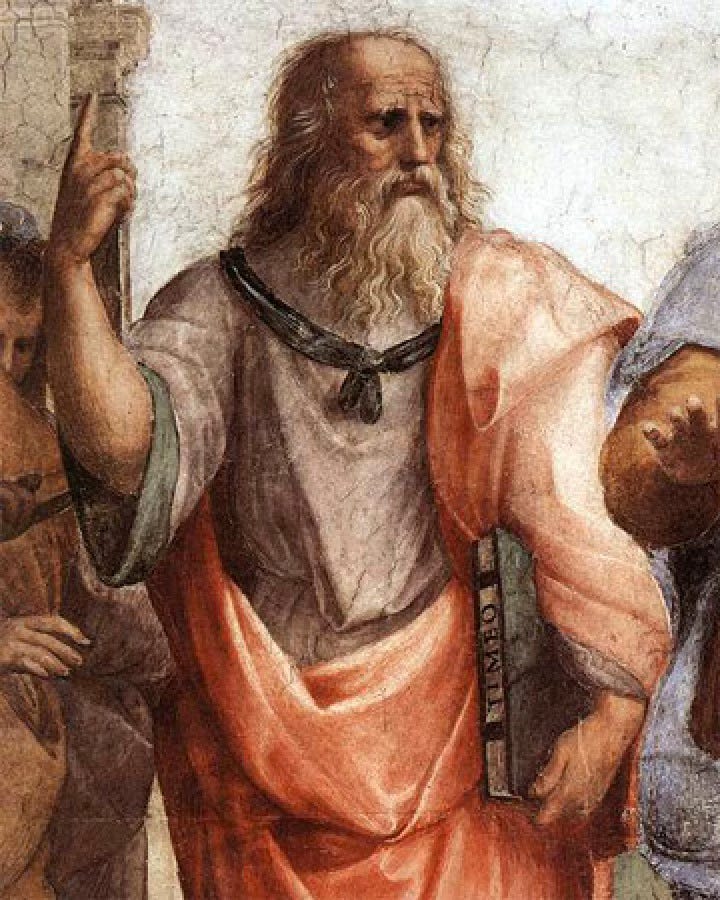

A quick one on civility and Plato’s old idea about human motivation

There’s a philosophical idea stretching back to Plato that goes roughly like this: people do things because they think doing those things is good.1 It’s very profound, I know. More precisely, the idea is that humans are (generally) motivated to pursue goals because they take those goals to be desirable (worth pursing). This is called the guise of the good thesis (GG).

Of course, what is desirable is not always actually good, and what is good is not always desirable. Sometimes, people pursue goals that seem bad for them or maybe even evil, which may seem odd. But it will seem less odd if you believe that they do it because they think that bad thing is actually good. They could be seriously wrong, but trying to take their perspective is not just explanatorily helpful but politically helpful too.

Civility, the virtue of showing respect even amid disagreement, sits comfortably with this view of human motivation. It’s easier to be civil when you think others are pursuing what seems good to them, rather than merely defecting from what seems good to you.

This is, admittedly, an empirical claim. It would be supported by showing that it really is psychologically easier to be civil when one believes in GG. Conversely, it could be supported by showing that it’s harder if you don’t adopt something like GG.

Here are two studies that point in that direction.

Curtis Puryear and colleagues studied what they call a “basic morality” bias. Basically, Democrats and Republicans overestimate the percentage of people in the opposing party who approve of widely agreed-upon moral wrongs, such as theft, cheating on one’s spouse or animal abuse. They detected this by looking at the social media posts of 5,806 US partisans – where liberals were called ‘baby murderers’ and conservatives ‘deplorable bigots’ – and a representative survey asking partisans to judge the other side’s support for immorality. If social media constantly bombards – and we don’t self-correct – us with the impression that our opponents are depraved, it’s no wonder we won’t want to talk to each other.

Interestingly, correcting the basic morality bias helps:

“Reminding partisans that people on the other side respect basic moral values may reduce dehumanization and increase their willingness to engage with opponents.”

It’s surprisingly simple but quite powerful. Try to keep in your head that your opponent is moral and it will be far easier to cooperate with them. A great step in the direction of such cooperation will likely involve communicating with them civilly.

Still though, the basic morality story can’t be enough to support my point. It’s easy to be civil when you discover your opponent also condemns theft and cruelty (who doesnt?) What about more controversial disagreements? What about non-basic morality?

A second 2016 study by Joshua Kalla and David Broockman revealed something interesting. In Florida field experiments, door-to-door canvassers held ten-minute, non-judgmental conversations with voters about transgender rights. Rather than arguing, canvassers asked voters to imagine life from a transgender person’s point of view or recall a time when they themselves felt discriminated against. Those brief perspective-taking conversations led to lasting reductions in prejudice—effects that persisted for months compared with standard advocacy scripts.2

It’s not a stretch to connect this to the guise of the good. Removing or softening the barriers to civility—prejudice, moral disgust, dehumanization—often begins when we see that others are, in their own way, trying to live by what they take to be good.

So, next time you’re in an online brawl or an in-person argument, think about Plato’s old idea. You might not find common ground, but you might find a common motivation. And that’s a solid foundation for civility.

“No one errs willingly or goes willingly toward the bad.” - Plato’s Protagoras.

This wasn’t just a one-off. They ran a second 2020 study about immigration that showed the same positive effect.

This notion is great, theoretically. But inevitably crippling. We are making (binary) decisions every single day.

How do I make a decision on which school to take my children, for instance? If I accept that every school is motivated by good then I decide to go with the one that I think is 'my kind of good'. I have then decided that the other school is sincerely wrong about some things. Next step is then to spend my energy ensuring that the 'sincerely wrong' school doesn't get more children or more government funding going to it. Then war begins.

Or perhaps in a kinder society, a rehabilitation programme for the alumni of the sincerely wrong school ;-)